Even if you've registered dongle–protected software on the developer's web site. A dongle: you can install the dongle drivers and associated utility software on. Your Syncrosoft dongles at any time, without requiring an Internet connection. Mar 25, 2013 - Its functionality was extended so far as to read out a real dongle, save the. Folder, I can run the software on multiple systems without a dongle.

Jump to navigationJump to searchA software protection dongle (commonly known as a dongle or key) is an electronic copy protection and content protection device. When conncted to a computer or other electronics, they unlock software functionality or decode content.[1] The hardware key is programmed with a product key or other cryptographic protection mechanism and functions via an electrical connector to an external bus of the computer or appliance.[2]

In software protection, dongles are two-interface security tokens with transient data flow with a pull communication that reads security data from the dongle. In the absence of these dongles, certain software may run only in a restricted mode, or not at all. Shin gundam musou 2. Apart from software protection, dongles can enable functions in electronic devices, such as receiving and processing encoded video streams on television sets.

- 1History

History[edit]

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Wordcraft became the earliest program to use a software protection dongle.[3] The dongle was passive, using a 74LS165 8-bit shift register connected to one of the two tape cassette ports on the Commodore PET microcomputer. The tape cassette port supplied both power and bi-directional data I/O.

The requirements for security were identified by the author of the Wordcraft word processor, Pete Dowson, and his colleague Mike Lake. Through the network of PET users in the UK they made contact with Graham Heggie in Coventry. Graham's knowledge of electronics helped to speed up their creation of a 74LS165 shift register connected to the tape cassette port which provided 5V power and lines to shift the bits into the software. The shift register contained only 8-bits, but with lines tied to ground or 5V at random it could provide a random number between 0 and 255 which was sufficient security for the software. The prototype was on Veroboard which dangled from the tape port edge connector on wires - and 'dangle' eventually transformed into 'dongle'. Pete Dowson wrote special self-modifying 6502 machine code to drive the port directly and to obfuscate the code when not in use.

The first device used a commercial potting box with black or blue epoxy resin. Wordcraft's distributor at the time, Dataview Ltd., then based in Colchester, UK, went on to produce dongles for other software developers. When Wordcraft International was formed in Derby, UK, responsibility for manufacturing was transferred to Brian Edmundson who also produced the plastic moulding for the enclosure. One of the greatest regrets shared by Graham, Pete and Mike was that they did not patent their idea.[4]

Versions of the Wordcraft dongle were later produced for IBM 25 pin parallel ports, 25 pin serial ports and 9 pin serial ports. Among the computers supported, before the arrival of the IBM PC, were Chuck Peddle's Sirius Systems Technology Victor 9000, the ACT Apricot Computers and the DEC Rainbow 100.

An early example of the term was in 1984, when early production Sinclair QLs were shipped with part of the QL firmware held on an external 16 KB ROM cartridge (infamously known as the 'kludge' or 'dongle'), until the QL was redesigned to increase the internal ROM capacity from 32 to 48 KB.[5][6]

Dongles rapidly evolved into active devices that contained a serial transceiver (UART) and even a microprocessor to handle transactions with the host. Later versions adopted the USB interface, which became the preferred choice over the serial or parallel interface.

A 1992 advertisement for Rainbow Technologies claimed the word dongle was derived from the name 'Don Gall'. Though untrue, this has given rise to an urban myth.[7]

Usage[edit]

Efforts to introduce dongle copy-protection in the mainstream software market have met stiff resistance from users. Such copy-protection is more typically used with very expensive packages and vertical market software such as CAD/CAM software, MICROS Systems hospitality and special retail software, Digital Audio Workstation applications, and some translation memory packages.

In cases such as prepress and printing software, the dongle is encoded with a specific, per-user license key, which enables particular features in the target application. This is a form of tightly controlled licensing, which allows the vendor to engage in vendor lock-in and charge more than it would otherwise for the product. An example is the way Kodak licenses Prinergy to customers: When a computer-to-plate output device is sold to a customer, Prinergy's own license cost is provided separately to the customer, and the base price contains little more than the required licenses to output work to the device.USB dongles are also a big part of Steinberg's audio production and editing systems, such as Cubase, WaveLab, Hypersonic, HALion, and others. The dongle used by Steinberg's products is also known as a Steinberg Key. The Steinberg Key can be purchased separately from its counterpart applications and generally comes bundled with the 'Syncrosoft License Control Center' application, which is cross-platform compatible with both Mac OS X and Windows.

Some software developers use traditional USB flash drives as software license dongles that contain hardware serial numbers in conjunction with the stored device ID strings, which are generally not easily changed by an end-user. A developer can also use the dongle to store user settings or even a complete 'portable' version of the application. Not all flash drives are suitable for this use, as not all manufacturers install unique serial numbers into their devices. Although such medium security may deter a casual hacker, the lack of a processor core in the dongle to authenticate data, perform encryption/decryption, and execute inaccessible binary code makes such a passive dongle inappropriate for all but the lowest-priced software. A simpler and even less secure option is to use unpartitioned or unallocated storage in the dongle to store license data. Common USB flash drives are relatively inexpensive compared to dedicated security dongle devices, but reading and storing data in a flash drive are easy to intercept, alter, and bypass.

Issues[edit]

There are potential weaknesses in the implementation of the protocol between the dongle and the copy-controlled software. It requires considerable cunning to make this hard to crack. For example, a simple implementation might define a function to check for the dongle's presence, returning 'true' or 'false' accordingly, but the dongle requirement can be easily circumvented by modifying the software to always answer 'true'.

Modern dongles include built-in strong encryption and use fabrication techniques designed to thwart reverse engineering. Typical dongles also now contain non-volatile memory — essential parts of the software may actually be stored and executed on the dongle. Thus dongles have become secure cryptoprocessors that execute program instructions that may be input to the cryptoprocessor only in encrypted form. The original secure cryptoprocessor was designed for copy protection of personal computer software (see US Patent 4,168,396, Sept 18, 1979)[8] to provide more security than dongles could then provide. See also bus encryption.

Hardware cloning, where the dongle is emulated by a device driver, is also a threat to traditional dongles. To thwart this, some dongle vendors adopted smart card product, which is widely used in extremely rigid security requirement environments such as military and banking, in their dongle products.

Dongle Software Free Download

A more innovative modern dongle is designed with a code porting process which transfers encrypted parts of the software vendor's program code or license enforcement into a secure hardware environment (such as in a smart card OS, mentioned above). An ISV can port thousands of lines of important computer program code into the dongle.[citation needed]

Game consoles[edit]

Some unlicensed titles for game consoles (such as Super 3D Noah's Ark or Little Red Hood) used dongles to connect to officially licensed ROM cartridges, in order to circumvent the authentication chip embedded in the console.[citation needed]

Some cheat code devices, such as the GameShark and Action Replay use a dongle. Typically it attaches to the memory card slot of the system, with the disc based software refusing to work if the dongle is not detected. The dongle is also used for holding settings and storage of new codes, added either by the user or through official updates, because the disc, being read only, cannot store them. Some dongles will also double as normal memory cards.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Amos, S. W.; Amos, Roger S. (2002). Newnes Dictionary of Electronics (4th ed.). Newnes Press. p. 152. ISBN0750643315. OCLC144646016. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^Stobbs, Gregory A. (2012). Software Patents (Third ed.). Wolters Kluwer. pp. 2–90. ISBN9781454811978. OCLC802867781. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^https://qustuff.com/early_days.htm

- ^https://qustuff.com/early_days.htm

- ^Ian Adamson; Richard Kennedy. 'The Quantum Leap – to where?'. Sinclair and the 'Sunrise' Technology. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

- ^Rick Dickinson (2007-07-16). 'QL and Beyond'. Flickr. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^Sentinel advert, Byte Magazine, p. 33

- ^US Patent 4,168,396

External links[edit]

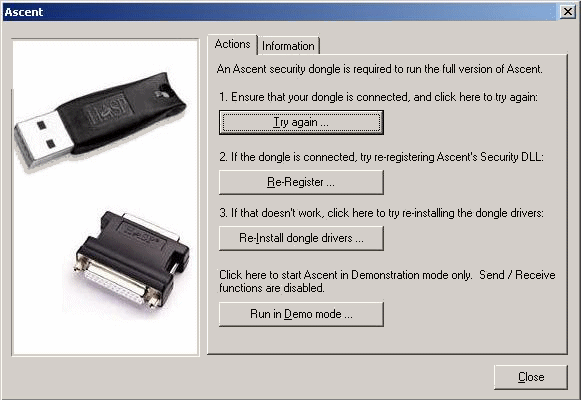

Various software companies distribute their software with hardware security, usually a dongle which must be mounted in order for the software to operate.

I don't have experience with them, but I wonder, do they really work?

What is it that the dongle actually does? I think that the only way to enforce security using this method, and prevent emulation of the hardware, the hardware has to perform some important function of the software, perhaps implement some algorithm, etc.

Dv Dongle Software

3 Answers

Clearly Peter has addressed the main points of proper implementation. Given that I have - without publishing the results - 'cracked' two different dongle systems in the past, I'd like to share my insights as well. user276 already hints, in part, at what the problem is.

Many software vendors think that they purchase some kind of security for their licensing model when licensing a dongle system. They couldn't be further from the truth. All they do is to get the tools that allow them to implement a relatively secure system (within the boundaries pointed out in Peters answer).

What is the problem with copy protection in general? If a software uses mathematically sound encryption for its licensing scheme this has no bearing on the security of the copy protection as such. Why? Well, you end up in a catch 22 situation. You don't trust the user (because the user could copy the software), so you encrypt stuff or use encryption somehow in your copy protection scheme. Alas, you need to have your private key in the product to use the encryption, which completely contradicts the notion of mistrusting the user. Dongles try to put the private key (and/or algorithm and/or other ingredients) into hardware such that the user has no access in the first place.

However, since many vendors are under the impression that they purchase security out of the box, they don't put effort into the correct implementation. Which brings me to the first example. It's a CAD program my mother was using. Out of the knowledge that dongles connecting to LPT tend to fail more often than their more recent USB counterparts, I set out to 'work around' this one. That was around 2005.

It didn't take me too long. In fact I used a simple DLL placement attack (the name under which the scenario later became known) to inject my code. And that code wasn't all too elaborate. Only one particular function returned the value the dongle would usually read out (serial number), and that was it. The rest of the functions I would pass through to the original DLL which the dongle vendor requires to be installed along with the driver.

The other dongle was a little before that. The problem here was that I was working for a subcontractor and we had limited access only to the software for which we were supposed to develop. It truly was a matter of bureaucracy between the company that licensed the software and the software vendor, but it caused major troubles for us. In this case it was a little more challenging to work around the dongle. First of all a driver had to be written to sniff the IRPs from and to the device. Then the algorithm used for encryption had to be found out. Luckily not all was done in hardware which provided the loop hole for us. In the end we had a little driver that would pose as the dongle. Its functionality was extended so far as to read out a real dongle, save the data (actually pass it to a user mode program saving it) and then load it back to pose as this dongle.

Conclusion: dongles, no matter which kind, if they implement core functionality of the program to which they belong will be hard to crack. For everything else it mostly depends on the determination and willingness to put in time of the person(s) that set out to work around the dongle.As such I would say that dongles pose a considerable hindrance - if implemented correctly - but in cases of negligence on part of the software vendor seeking to protect his creation also mere snake oil.

Take heed from the very last paragraph in Peters answer. But I would like to add one more thought. Software that is truly worth the effort of being protected, because it is unique in a sense, shouldn't be protected on the basis of customer harassment ( most copy protection schemes). Instead consider the example of IDA Pro, which can certainly be considered pretty unique software. They watermark the software to be able to track down the person that leaked a particular bundle. Of course, as we saw with the ESET leak, this doesn't help always, but it creates deterrence. It'll be less likely that a cracker group gets their hands on a copy, for example.

Problem description

Let's make a couple of assumptions. Software is divided into functional components. Licenses are for functional components within that software package. Licenses can be based on time, on version or on a number of uses, i.e you may use the functionality until a set point in time, you may the functionality of the version you purchased or some minor derivative of it or you may use it a number of times. There are two main scenarios you have to solve, where an attacker doesn't have access to a license and where he does.

Attacker with no license

The first scenario is where your attacker does not have access to a valid license to your product. This problem is easy to solve. Simply assign a separate encryption key to each of the functional licenseable parts of your software. Encrypt each functional part with the encryption key designed for that part. Now you can distribute your software without worry of someone being able to decrypt functions they have not licensed since you never send them the key.

Attacker with access to license

The second scenario, which is much harder to solve, is when your attacker has a valid license to your software but he either wants to redistribute the functions he has licensed or to extend his license time wise.

Now you need a reliable time source, this can be solved by:

- embedding a public key into a dongle and having the dongle issue a random challenge which must be forwarded to a time server. The time server responds by signing the current time and the challenge and returning it to the client which then sends it to the key and the key then updates its internal clock and unlocks.

- updating the internal clock based on the time it has been plugged into the computer. The USB port supplies power to your dongle all the time while its plugged in.

- updating the internal clock based on timestamps sent from drivers installed on the machine its attached to. Only allow timestamps forward in time. Only allow movement backwards in time if the time source is a remote trusted time server supplying a signed timestamp.

If your license is based on versions you actually have an attacked who does not have access to a license because your key derivation function for the functional unit takes both the identifier of the functional unit and the version of it as input.

Key distribution

So once you have separate keys for each functional unit your licenses basically becomes a matter of distributing symmetric keys so that they can be sent to the dongle. This is usually done by embedding a secret symmetric key in the dongle, encrypting the license decryption keys with the shared secret key and then signing the encrypted key update files. The signed update files are then passed to the dongle which validates the signature on the update, decrypts the new keys with the shared symmetric key and stores them for later use.

Key storage

All dongles must have access to secure storage in order to store license decryption keys, expiration timestamps and so on. In general this is not implemented on external flash memory or EEPROM. If it is it must be encrypted with a key internal to the ASIC or FPGA and signed such that it can not be changed.

Plain text hole

Once the user has a license to your functional component, even if he can't extract your secret key, he can use your dongle to decrypt that functional component. This leads to the issue that he may extract all your plain text and replace the decryption call with a direct call to the extracted plain text. Some dongles cover this issue by embedding a processor into the dongle. The functional component is then sent encrypted over to the dongle which decrypts the component and executes it internally. This means that the dongle essentially becomes a black box and the functional components sent to the dongle needs to be probed individually to discover their properties.

Oracles

A lot of dongles are encryption and decryption oracles which leads to potential issues with Chosen-ciphertext attacks, e.g the recent padding oracle attacks.

Side channel attacks

Besides the oracle issues you also have a lot of concerns with all of the so far well known side channel attacks. You also need to be concerned with any potential but undiscovered side channel.

Decapsulation

Logitech Dongle Software

Be aware that there are a number of companies in the world who specialize in picking apart and auditing secure chips. Some of the most well known companies are probably Chris Tarnovsky of flylogic, now part of IOActive and chipworks. This sort of attack is expensive but may be a real threat depending on the value of your target. It would surprise me if but a few, possibly none of, dongles today are able to withstand this sort of high budget attacker.

Do they work

Given a dongle which is based on strong encryption, isn't time based since you can not expire encryption keys based on time nor is time an absolute, free of any side channel attacks and executes the code on the chip, yes it will make discovering the underlying code equivalent to probing a black box. Most of the breaks that happen with these dongles are based on implementation weaknesses by the licensees of the hardware licensing system due to the implementer being unfamiliar with reverse engineering and computer security in general.

Also, do realize that even software where a majority of the logic is implemented on an internet facing server has been broken simply by probing the black box and inferring server side code based on client code expectations. Always prepare for your application to be broken and develop a plan for how to deal with it when it happens.

As Peter has indicated, looking at how the dongle is used for security is the starting point to identify the attack vectors. In most cases, the software developers implementing the dongle security is the weakest point.

In the past when I have tested software with dongles, I have used free tools like ProcessMonitor and RegShot to identify simple vulnerabilities to defeat bad implementations of dongle security.

I have seen software that on startup checks for the presence of dongle and then proceeds with its operation without using the dongle until its restarted. In these cases, patching the application with OllyDbg is not that difficult to tell the app to run with full functionality as long as the dongle is NOT plugged in to the system.

I have also seen software that allows a user to click on a button in the software so that the user doesn't have to have the dongle inserted. The software claimed that is an extra functionality like 'Remember Me' option. RegShot and ProcessMonitor showed me that a file is written with some information and as long as the file is present in the expected folder, I can run the software on multiple systems without a dongle.

Just because someone uses AES or Hardware Dongles or any XYZ doesn't mean they are secure. All that maters is whether they are implementing those security measure in the right manner assuming that there are now known (or 0-day vulnerabilities) in the security measure.

protected by Community♦Nov 9 '15 at 12:26

Thank you for your interest in this question. Because it has attracted low-quality or spam answers that had to be removed, posting an answer now requires 10 reputation on this site (the association bonus does not count).

Would you like to answer one of these unanswered questions instead?